A Guide to Rotations. For the Mentor and Mentee

Hello, my name is Raul Ramos and as of Fall 2020, I am a 6th year Neuroscience Ph.D. student at Brandeis University. This commentary is my informal advice to rotation students and mentors. In my time as a graduate student, I rotated through 4 different labs, that’s 4 different experiences as a mentee, and I have mentored 4 PhD rotation students. I can happily report that my mentees have had successful rotation experiences. However, this wasn’t just happenstance. It was a result of purposeful effort between them and myself. My drive to provide students with a positive experience and a supportive learning environment was fueled by my own experiences as a mentee, and the shortcomings I witnessed on both sides of the aisle. I saw firsthand how the combination of inexperience and bad mentorship could disastrously derail a precious rotation. Honestly, a bad rotation can be traumatic. This puts a lot of pressure on the primary mentor which is often a fellow graduate student. So, because of the experiences shared with me, my own experience, and the significance of a rotation, I have put together this document of advice for both the mentee and mentors alike. As always, I hope this helps you in some way.

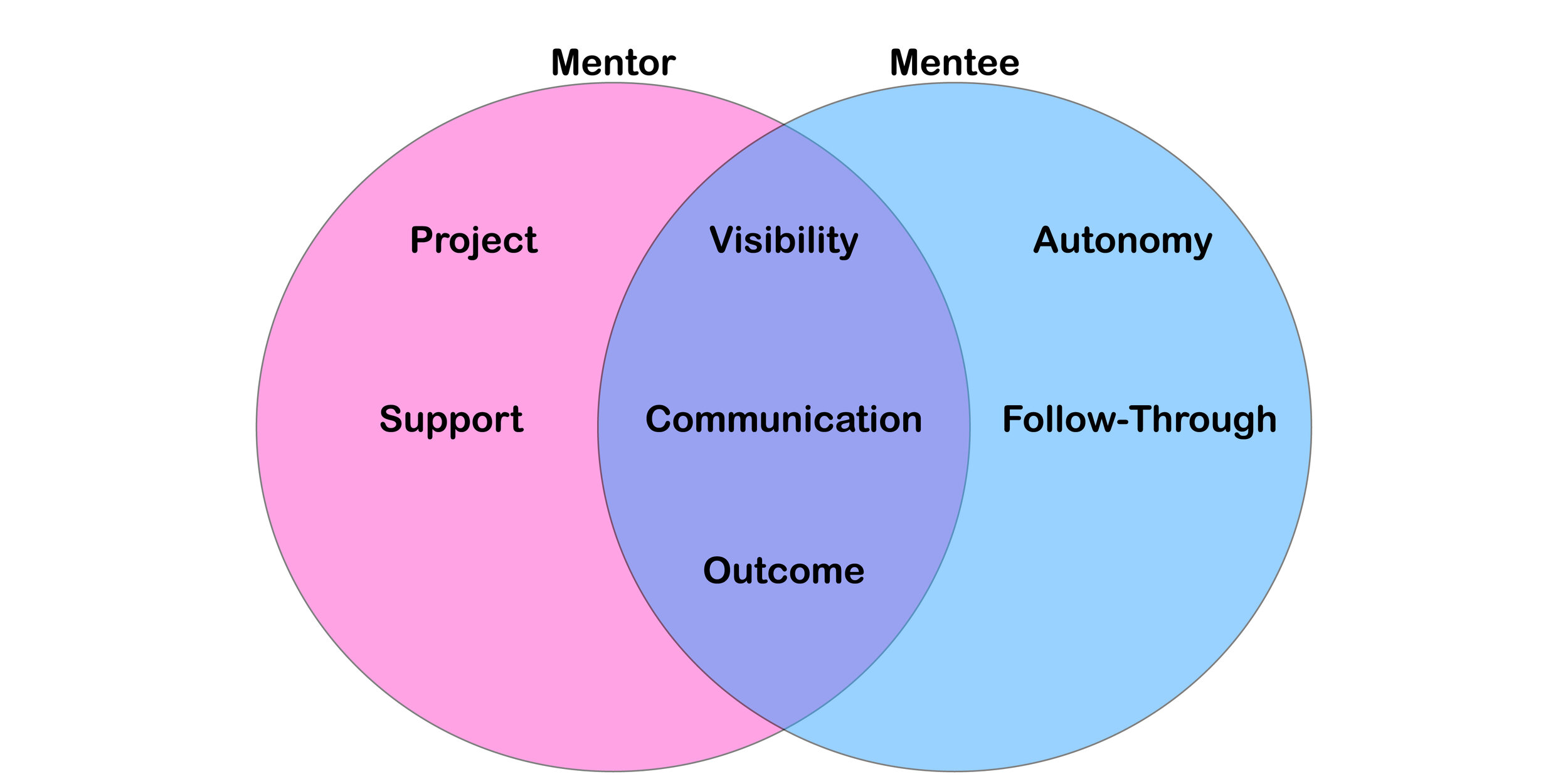

To help simplify this discussion, I created a Venn diagram of responsibilities (Figure 1). My goal here is to clearly outline some of the key factors that I believe weigh heavily during a rotation and delineate the primary stakeholder. Now, this by no-means is a definitive guide, and I am sure that there are many more wonderful perspectives out in the world. Hopefully, this essay will serve as a catalyst for discussion and I can update it in the future. For now, I will break down these individual aspects and offer a perspective for both the mentor and the mentee where it is available.

Figure 1

Project, For the Mentor: I can’t emphasize this enough, choosing a rotation project is not easy and it is incredibly important. The project you choose will lay the foundation for the road ahead of you, and for the challenges your mentee will face. I 100% recommend having a few ideas always ready to go and discussing them with your PI and senior members of the lab. What I look for in a potential rotation project is feasibility, opportunity for learning, and utility. First, you want a project that is feasible for the rotation student to follow through on. DO NOT assign them to projects that require ordering a reagent or piece of equipment that will not arrive on time (this happened to me during my 2nd rotation! It sucked). Rotations at Brandeis are 9 weeks, always keep in mind the length that you are working with and plan out a rough timeline for meeting different objectives of the experiment. For example, I usually plan two weeks of reading and shadowing, five weeks of running experiments, one week of analyzing data, and then one week for preparing a presentation (all our rotation students present in lab meeting). Choosing a feasible project will make this a positive experience for everyone. The next thing you want in a project is to make sure that there is an opportunity for learning. How do you do this? By communicating with your mentee! I will dig more deeply into communication, but usually students choose to rotate through a lab because they want to learn a specific set of skills (like patch-clamp). Nothing is more demoralizing to your mentee than not being heard from the get-go, talk to them and choose a project that allows them to learn new things. I like to choose projects that give my students an opportunity to learn at least 3 new skills (that includes an analysis method). For example, my last rotation student learned about virus injections, animal handling, whole-cell electrophysiology and he analyzed his own data. The last key component to a good rotation project, in my opinion, is utility. Having a rotation student is always a significant time investment for everyone, there is no way around that. So, choosing a project that is actually useful for you is very intrinsically motivating. Because of all these factors, I really enjoy having rotation students work on control experiments or supplemental experiments that I never had the time for. Usually, these kinds of experiments have a very defined approach, path to completion and I am usually familiar with the timeline and how much training I will have to invest. You may be tempted to have a mentee develop their own project, but there often isn’t enough time for that. A failed project can be really demoralizing, and it is just not worth it. Hopefully, taking these factors into account will provide a rough guide for generating rotation project ideas.

Project, For the Mentee: Do your homework and be ready to communicate what it is you really want to learn during your rotation. You are your best, and at times your only, advocate.

Support, For the Mentor: Once you have chosen a project, your primary responsibility is supporting them on their journey. This means teaching your mentee the skills needed to follow through and guiding them towards autonomy (that will be discussed later). Make sure you clearly communicate expectations, set goals, and check in. A rotation doesn’t end when the experiments are done, be available for analysis and help with any final benchmarks. At Brandeis, this means help your students craft their end of rotation presentation! No one wants to watch a mentee crash and burn during lab meeting (it happens, unfortunately). Things will get tough, remember that science is a team sport and your mentees are adult humans with feelings! Being a mentor seldom ends with the rotation.

Support, For the Mentee: Your mentor will not always be supportive, unfortunately, bad matches happen. Every graduate program is rife with nightmare stories, and that’s the truth. So, what do you do when you aren’t being supported by your mentor? Have allies everywhere. Have faculty members that are your allies, have senior graduate students that you can talk with, lean on your cohort. These three things are so important for the entirety of your graduate school career, and probably beyond.

Visibility, For the Mentor: Labs are social environments and it can feel really intimidating as a new, transient, rotation student. Mentors, take a morning to walk your mentee through the lab and introduce them to other people. Invite your mentee to lunch with you. Be friendly, do not let your mentee become invisible.

Visibility, For the Mentee: Mentees, labs are social environments and you want the people who work in them to like you (or at the minimum not dislike you). Many PI’s ask their lab if they are ok with X person joining. This could be challenging if you are more introverted, but people need to get to know you, so make a plan. I usually advise my students to schedule at least one short meeting with everyone in the lab. If you are shy, focus the conversation on research. This will increase your visibility and it gives you an opportunity to learn about all the cool projects happening in the lab. If your mentor doesn’t push you on this, take initiative, people know you are new and will likely be very friendly. If they are not friendly, that is also something you want to know. Lastly, I always have my mentees schedule a mid-rotation check in, and a post-rotation check in with our PI (they have usually had an initial meeting before starting in the lab). Some students set up weekly or bi-weekly check ins with the PI, you’re allowed to communicate a schedule that fits your needs. Ultimately, this will be your advisor for the next 5-7 years! You want to know what they are like, how they mentor, and whether it is a good fit for you or not.

Communication, For the Mentor: It is incredibly important that both the mentor and the mentee communicate. You would think that I don’t need to say this, but so many bad rotations boil down to a failure to communicate expectations. My approach is to have a meeting as soon as I know I will be working with a new student. Mentors, schedule a time to meet with your mentee as soon as it is feasible for the both of you. During this meeting you will want to ask your rotation student what it is they want to get out of this experience, you’ll want to communicate project ideas that may align with the students interests, and you will want to clearly communicate your expectations (and don’t be flip-floppy). Ultimately, this is their rotation and we are a facilitator and a teacher.

Communication, For the Mentees: Mentees, if your rotation mentor does not clearly outline what your project is and their expectations or if they do not ask you what you are interested in learning, these are BIG red flags. However, do not panic, it is possible that your mentor is inexperienced or introverted. Take initiative and say that you want to meet and talk about your rotation. Ask them to clearly explain the project and what they expect for you to learn. This is your career and now is not a time to be short of words, or questions. This extends to meetings with the PI and is especially true when you are discussing a potential rotation in their lab. For example, during one of my rotations, because I was new and inexperienced, I did not ask the PI if they were looking for new PhD students. I only asked if I could rotate in the lab and expressed that I was excited to do so. I began rotating in the lab, thinking I could become a permanent member, only to find out several weeks later that the PI wasn’t looking for new students. It was crushing. Communication is key. Don’t hold back your questions, ask about everything.

Autonomy, For the Mentor: See support section

Autonomy, For the Mentee: This is my personal thermometer, as both a student and a teacher, for how well a rotation is progressing. As a student, it is important to strive for autonomy in the lab because it clearly demonstrates, through actions, that you are learning. This was always my personal goal, and I always push my rotation students to reach this benchmark. However, I want to make sure there is no ambiguity here. Science is a team sport, autonomy does not mean your mentor stops supporting you, or that you stop interacting with other lab members. It means that you are able to carry out, mostly on your own, some of the techniques you have been learning. Realistically, be aware that this doesn’t always happen and that’s ok. For example, I was only autonomous in 2 out of 4 rotations, the first two were just bad matches. If you are on a bad project or you have not received any support or training, you can’t be autonomous and that’s not your fault.

Follow Through, For the Mentor: Mentors, if you have done your homework and chosen a thoughtful project, this is where you want to give your mentees room to shine. Teach them and support them in their endeavors. Check in everyday and make sure they do not fall in-between the cracks, but let them do their own work. Giving students the space to take things into their own hands creates an opportunity for their personality and flair to come through. You’ll be surprised by the creative ways in which students tackle challenges in the lab.

Follow Through, For the Mentee1: Mentees, this is your time to shine. You can think of a rotation as one long job interview. It is a professional environment and you want to demonstrate that you’re a good candidate. This doesn’t mean being a prodigy, it means learning what is being taught and reaching reasonable mile-stones (as outlined above). Never forget that you are being professionally evaluated by everyone in the lab all the time. People want to know if you will be a constructive addition to the lab. Some of the things you will be evaluated for, on top of “autonomy”, include:

· Did you show up to lab when you said you would? Time management and scheduling are critical. Our work lives often revolve around the equipment calendars, not showing up makes people very grumpy.

· Super important: Did you demonstrate intellectual ownership of your project? That is, did you understand your project, ask questions to challenge that understanding and then follow through on the meaning of your experiments, i.e. did you get the big picture

If you take all these things into account, you should be able to navigate a rotation successfully. I realize that life happens and it can challenge your ability to lean into a rotation. Don’t be afraid to communicate these things to your mentor (if you feel comfortable).

Outcome: The outcome of any given rotation is a result of both the mentor and the mentee. However, it is also the result of many different life variables, some of which exert their influence outside the lab. I would consider a successful rotation to be one in which the student has met their goals as outlined at the beginning. This is a reasonable outcome if the goals stand upon a thoughtful foundation. This is particularly true if you have established these goals together as a team. I hope that what this essay has made clear is that a good rotation rests on a strong foundation and requires a lot of work from everyone. If you have picked a thoughtful project, if you’re ready to teach (mentors) and if you’re ready to learn (students) everything else should fall into place. There will be bumps along the way, but having an open channel of communication will help both parties navigate the bumps. I hope this essay provides a rough map and helps both mentors and mentees in their future rotation endeavors.

1. I would like to thank Avi Rodal for sharing some of the criteria that her lab uses to evaluate rotation students. She did not endorse this article in anyway and the opinions expressed here are my own.

Update 10/19/20: Avi has endorsed this article